Some Main Considerations & Assumptions

- Most African ancestors for Cape Verdeans are likely to have arrived in Cape Verde in the early colonial period 1460-1660. Because Cape Verde’s regional entrepot function was being taken over by Cacheu in Guiné Bissau already during the early 1600’s. Although slavery only got abolished in 1878 it is assumed by some historians that already in the late 1600’s a majority of the Cape Verdean population consisted of free blacks or mulattos being involved in selfsustaining rural activities. This because of widespread manumission, fleeing of slaves, socially accepted miscegenation and a collapse of most slave trade orientated activities during the 1600’s.

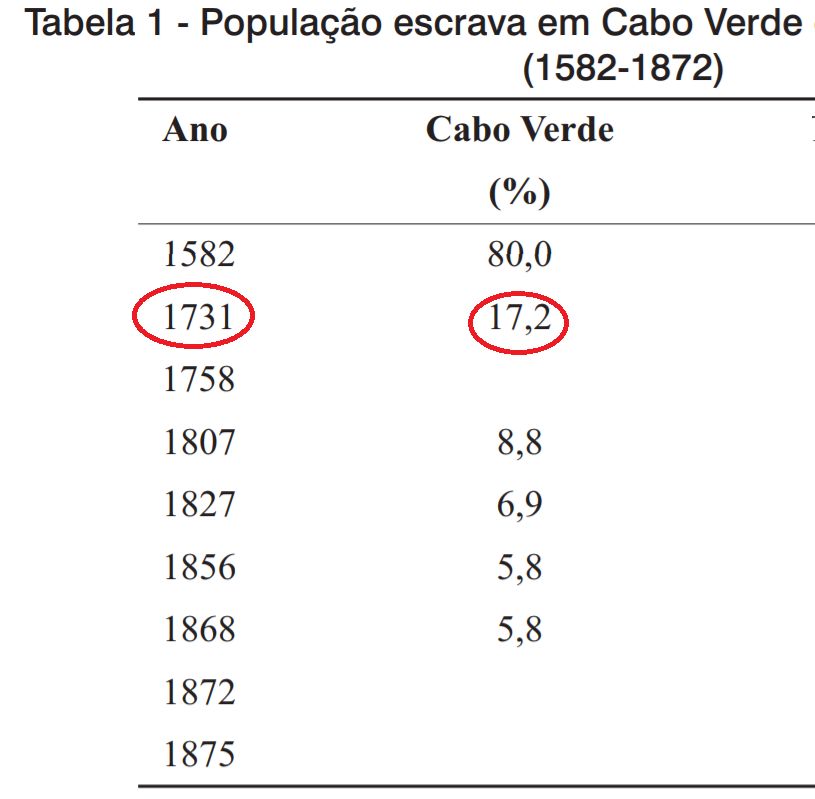

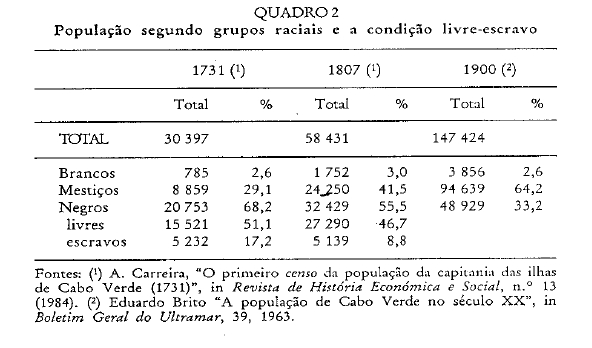

- We can find confirmation for this from the census held in 1731. Slaves (“escravos”) are being shown as less than 20% of total population and free blacks & mulattos (“mestiços”) already formed a clear majority of 80% in 1731. In 1807 the enslaved part of the population would even be less than 10%. So we can assume that for a majority of Cape Verdeans the African part of their ethnogenesis dates mostly from the period before 1731 at the very least and most likely especially the 1500’s playing a crucial part.

***

Population Share of Enslaved People in Cape Verde (1582-1872)

Table 1 (click to enlarge)

***

Racial Census Data for 1731, 1807 and 1900

Table 2 (click to enlarge)

***

***

- However a minor degree of slave labour was still maintained right till the end of slavery in 1879. Often employed in the mostly stagnant export sectors of cotton, panos (textiles) and salt. But also as domestic servants. It seems that famines in Cape Verde were much more deadly in the 1700’s/1800’s than in the early period (1400’s-1600’s). Sometimes killing more than half of the population! This could have meant that replacement by African born slaves was more frequent in later periods than in the 1500’s/1600’s when a high degree of native born “creole” slaves was reported for Cape Verde.

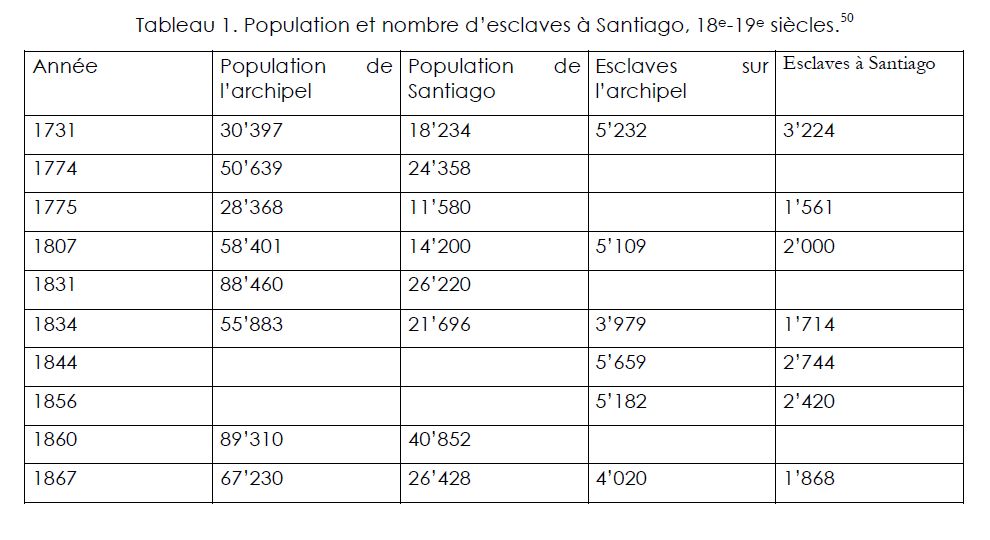

- So for a subset of Cape Verde’s population there was still continued African geneflow also in the 1700’s/1800’s leading perhaps to some differentiation in African ethnic origins between islands as well as socially defined subgroups on the same island. DNA research has already shown this to be the case to some degree. This chart below is showing the number of slaves in later periods and also how close to 50% of them were located on Santiago. However their relative share in the Santiago population itself remained below 20%.

***

Census Data for Cape Verde & Santiago, 1731-1867

Table 3 (click to enlarge)

***

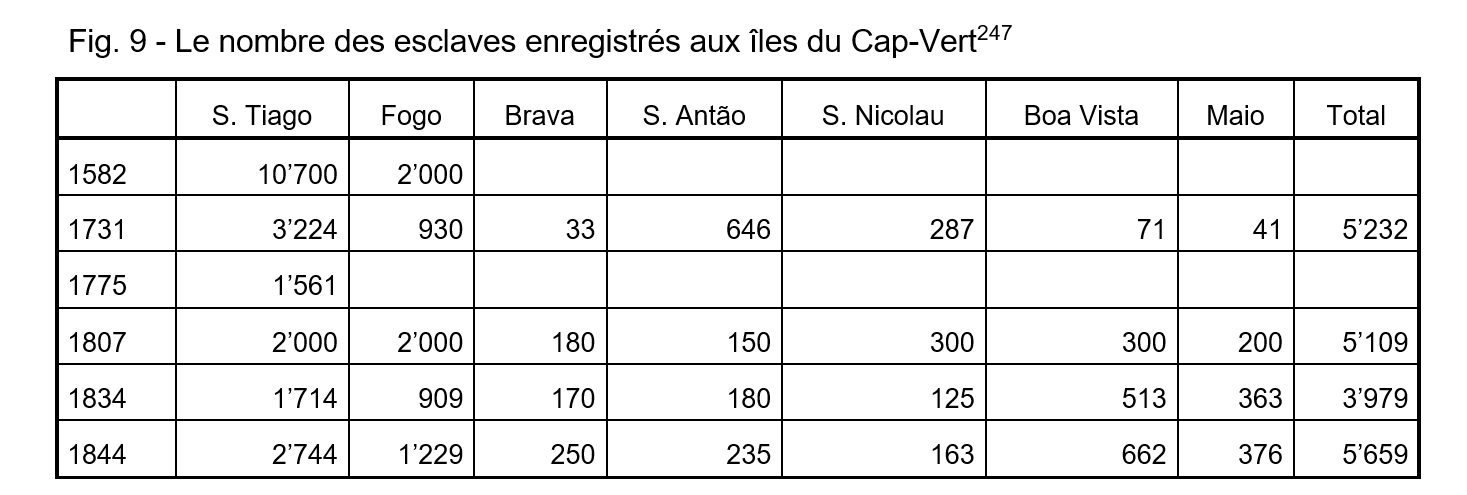

- In the following charts more details also for each separate island. Tables taken from an unpublished thesis by Rudolf Paul Widmer. Proportionally speaking it seems that Fogo had the highest relative share of enslaved people in its population. Almost 25% in 1731 and around 15% during the 1800’s. Also remarkable increase of enslaved persons on Boavista and Maio during the 1800’s. Regrettably no data available for Sal. But in both cases most likely linked to salt mining. Notice that on Santo Antão (the second-most populated island) and also São Nicolau the number of enslaved persons was however decreasing!

***

Number of slaves for each island, 1582-1844

Table 4 (click to enlarge)

***

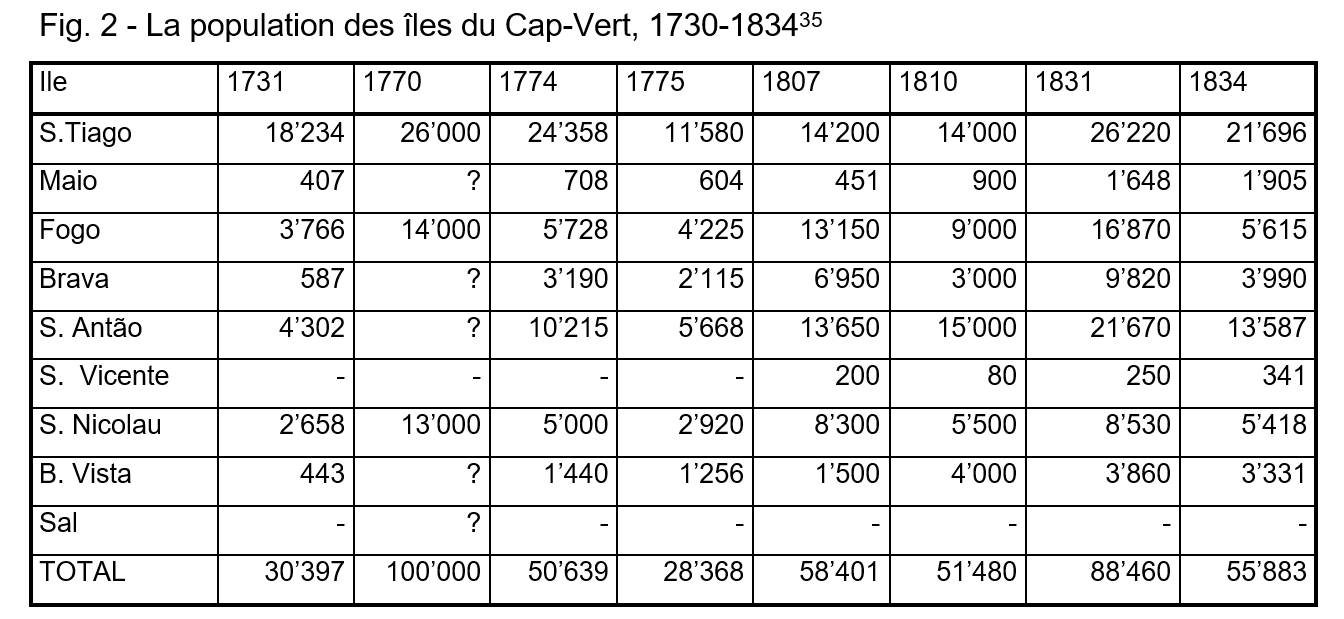

Total population numbers for each island, 1730-1834

Table 5 (click to enlarge)

***

- It has been suggested by some researchers that early adapting/creolizing slaves may have had a better survival ratio and could therefore be expected to pass on their genes disproportionally to their numbers. Because of a lack of European women, interracial unions took place right from the start in Cape Verde and many travellers took notice of the growing mulatto segment of the population. In 1620 the situation even prompted the Spanish king Phillip III (at that time also reigning over Portugal and its colonies) to send over Iberian women to Cape Verde to “extinguish the mulatto race”. To no avail however. See also Table 2 which shows a steadily increasing share of “mestiços” from 29.1% in 1731 to 64.2% in 1900.

- Because of social stigma it might be that this mixed-race group was relatively endogamous or at least more averse to intermarrying with African-born slave women than freed blacks (“forro’s”) who are known to have urged for legislation in the 1700’s enabling them to do so. The free blacks, a.k.a. Badius, of Santiago are also known to always having their numbers replenished with recent runaway slaves. If this were to be true even to a partial degree it could mean that the mulattos or mestiços from the census might have “timecapsuled” the African part of their mixed ancestry dating from the 1400’s-1600’s more so than freed blacks/forros.

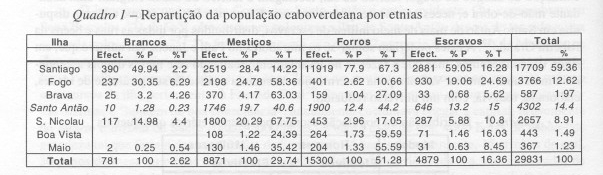

- Many of these mixed people would later on be prominent among those sent out to to settle the islands of the north in the late 1600’s/1700’s. This detailed breakdown of the 1731 census shows the ethnic composition for each island (in the third column of each category). It can be seen that mixed people (mestiços) were most important proportionally speaking in Santo Antão, São Nicolau, Brava and Fogo.

***

1731 census details for each island

Table 6 (click to enlarge)

***

- Cape Verde’s early history as a regional entrepot (1462-1647), constantly re-exporting slaves to Iberia, other Macronesian islandgroups (Canaries, Madeira and Açores) and the Spanish Americas, complicates things greatly. We don’t know for sure which slaves were kept on the island and which ones were sold on. Could any selection procedure possibly create ethnic bias? Several factors would have come into play; no doubt short term profitability was important but also the added value of keeping certain experienced and/or trusted slaves on the islands. Perhaps also being reinforced by social norms against selling domestic or socalled criado slaves except during times of extreme need like famines.

- These social norms of retaining trusted slaves (escravo de confiança) have been reported in the same time period for Luso Africans residing in Senegal & Guiné Bissau. Plus it was also cultural practice among many slaveholding ethnicities throughout West Africa. Cape Verde being known for turning African born slaves into Ladino slaves (baptism + basic Portuguese language skills). It could be that they were prominent among slaves being exported. However besides Bozales (“fresh of the boat” slaves) and Ladino’s a third distinction was made (according to Sandoval 1624) of socalled Naturales, that is Cape Verde born slaves. They were the most expensive but judging from slave trade registers only rarely to be seen in Latin America. Therefore possibly maintaining to some degree the ethnic composition of Cape Verdean slaves as it was during the very early settlement period.

- Cape Verde-based slave traders and their closely connected Luso-African/Lançado counterparts operated throughout Upper Guinea a.k.a. Guiné de Cabo Verde. Basically the area demarcated by the river Senegal in the north and the peninsula of Sierra Leone (Freetown) in the south. The arrival of North European competitors meant that Cape Verde based traders started to limit their activities already during the late 1500’s. First retreating from northern Senegal and later on also from Sierra Leone and Gambia, getting restricted to the area of Guiné Bissau and Casamance (southern Senegal).

- The Lançados and their Luso African offspring however were able to endure longer in most areas of Upper Guinea. They were opportunistically mainly dealing with those who offered the best prices. And so they became the preferred middlemen for the English/French and briefly also the Dutch. But because of cultural reasons they still kept in touch with Cape Verde-based traders as well. There’s evidence of their commercial activities as well as cultural survival (speaking Crioulo and being nominally Catholic) up till the late 1700’s in Senegal’s socalled Petit Coté (coastal line from Dakar to Gambia). They were only commercially relevant there till the late 1600’s though. In Gambia the Luso Africans were however very active still till the 1730’s, only disappearing in the 1780’s or so. Same goes for Guiné Conakry (Pongo & Nunez rivers) and Sierra Leone (northern part near Freetown). During the era of illegal slavetrading (1810’s-1840’s) these areas got visited again by slave traders based in Guiné Bissau.

- Ethnic references covering all of Upper Guinea can therefore be found during all periods for slaves present in Cape Verde. This can clearly be seen from the slave census taken in 1856 I will post in the next section. So there seems to have always been some degree of “multisourcing” which resulted in an ethnic and intraregional mix among Cape Verdean slaves. Still depending on political & commercial circumstances the “hot spots” for slave sourcing shifted across Upper Guinea. Generalizing I would say:

- 1460-1500: mainly northern Senegal (Wolof empire)

- 1500-1560: mainly breakaway provinces of the Wolof empire on the Petit Coté and the Casanga kingdom in Casamance.

- 1560-1600: mainly Sierra Leone (Mande invasions) and Rio Grande area (Guinala) in Guiné Bissau

- 1600-1700: mainly Cacheu (Guiné Bissau), however this was an entrepot for slaves not only from the surrounding area but also from Gambia, Casamance, Guinea Conakry and Sierra Leone in this period.

- 1700-1840’s: mainly Kaabu located in the interior of Guiné Bissau (via Farim/Gebu), because of the English and French ban on slave trade in the early 1800’s there was also some minor detour of slave caravans coming from interior of Senegal/Mali.

- Some Africans or mixed African descended people arrived in Cape Verde out of their free will. Even though obviously only a minority! We have scattered evidence for this occurring throughout Cape Verde’s history, right from the start. The fleeing Wolof prince Bemoim in the 1480’s probably being most well known. These were mainly people with nobility background or involved in regional trading. Typically they would convert to Christianity in order to fit into the Cape Verdean society. Some Africans also sent their children to Cape Verde to be educated in Portuguese in order to enhance their trading skills.

- From contemporary travelling reports (1500’s/1600’s) the following ethnicities have been mentioned: Wolof, Fula, Mandinga, Banhun, Beafada, Sape. Not by coincidence these were also the peoples who maintained the most cordial relations with Portuguese/Cape Verdean traders. There might have been others as well though. From Almada (1594):

- Besides them there were also many Lançados or their Luso-African offspring wanting to return to Cape Verde for their “retirement”. They might have brought along African wive(s) and their children plus a great number of domestic servants. This being pretty much standard in those days for those with social prestige. The Cape Verde-born writer Lemos Coelho from the late 1600’s is a good example. He left Cape Verde when he was only a youth joining a family business of mainland trading which was already started by his grandfather, uncles and many cousins. For around 20 years he stayed in several places within presentday Guinea Bissau and also Gambia. Apparently after he made his fortune he decided to return to Cape Verde and enjoy an early retirement. Even in the late 1700’s when the scattered Luso-African communities started to dwindle fast we have a report of a trader based in Sierra Leone, asking for a Cape Verdean priest and wanting “to die among Christians”.