LINGUISTICS

Over 95% of the Cape Verdean lexicon is drawn from Portuguese. However, it has also been strongly influenced by West-African languages (notably Wolof and Mandinga), especially in regards to verbal morphology and semantic structure. Research into the African influences on Cape Verdean Crioulo is still in full progress. African influence not being limited to just vocabulary but especially to be observed in grammar, expressions, pronunciation etc..

Also Cape Verdean toponyms sometimes can be traced to Upper Guinean origins. Most linguists have focused only on the variant spoken in Santiago (Badiu). Because its number of speakers is the biggest and also because this variant is the oldest one (besides Fogo). And therefore most likely shows the greatest African influence. However research into Crioulo variants spoken on other islands might produce new insights as well. I’ll just post some quotes and charts on the main outcomes sofar. It seems that Mandinga & Wolof by far are the main influence.

Of course linguistics isn’t always correlated with ancestral connections. Especially Mandinga has always been a widely used lingua franca throughout Upper Guinea for trading purposes but also among heavily Mandinganized peoples like the Banhuns, Beafada and Cassanga. Historically the Wolof language seems to have been more restricted. Although it is repeatedly said in accounts from the 1500’s/1600’s that both the Fula and Sereer were able to understand or even speak it. Given the overlap between these 3 languages I suppose it’s possible that some words being identified as having Wolof origin might actually be derived from either Sereer or Fula.

Wolof influences would have entered Crioulo in its earliest formation (1400’s/1500’s), while Mandinga influence might have been present already in the 1500’s but especially dominating in the 1700’s. We have testimony from an English traveller in the 1720’s who described the Crioulo spoken on the island of Brava as containing many Mandinga words.

____________________

“who hallowed and hoop’d much after the Manner of the Mandingo Negro’s;

from whom, I believe they might take their Original, being very like

them in Gesture, Manners, and Physiognomy, and

using a great deal of the Mandingo Dialect in their Speech.”Source: : http://archive.org/stream/fouryearsv…egoog_djvu.txt

**

These are my main sources:

- “Africanismos na língua caboverdiana (variante de Santiago)”, Nicolas Quint (2008)

- “Upper Guinea Creole Evidence in favor of a Santiago birth”, Bart Jacobs (2010)

- “A Wolof trace in the verbal system of the Portuguese Creole of Santiago Island (Cape Verde)”, Jürgen Lang (2011)

- Parallel Trajectories of Genetic and Linguistic Admixture in a Genetically Admixed Creole Population (Verdu et al., 2017)

**

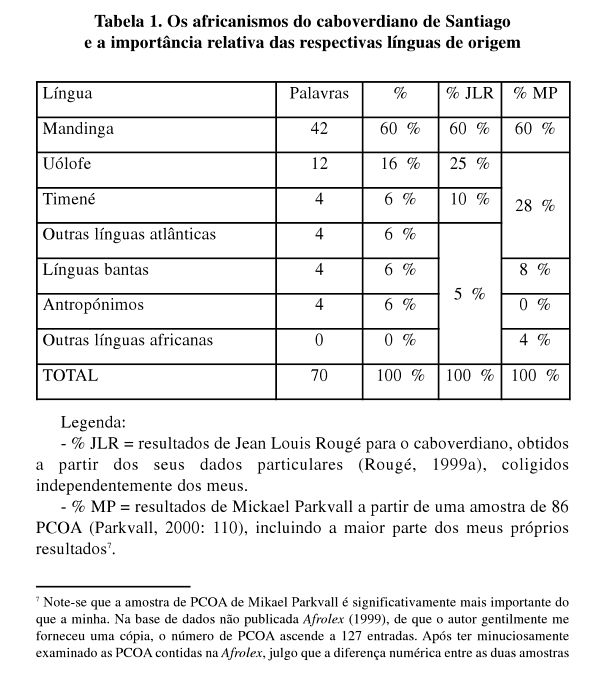

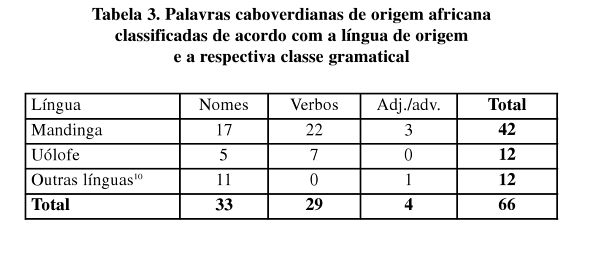

Quint (2008).

He describes 70 words found in Santiago Crioulo with certified African origins. He mentions however that this sort of research has only just started and expects eventually there might be 200-300 words of African origin to be identified in Cape Verdean Crioulo. Here’s the breakdown of the 70 he classified. Mandinga & Wolof (=Uolofe) clearly being dominant and also the only ones to provide verbs indicating that these two languages had a far more important role than the other African languages in the genesis of Cape Verdean Crioulo.

***

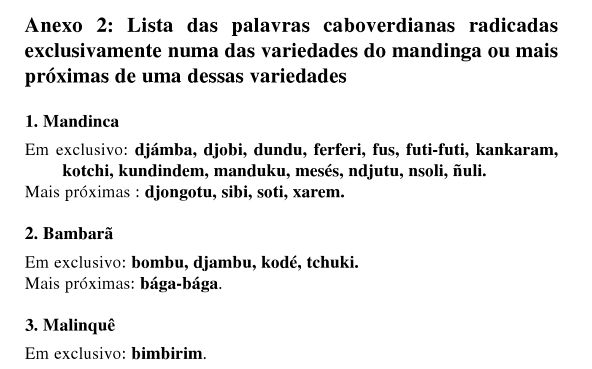

Mande origins are given for 60% of all words. Obviously the Mande languages have had their own evolution ever since it started influencing Cape Verdean Crioulo most likely already 5 centuries ago. So some words might represent antique versions of currentday words in Mande languages. Quint makes a speculative comparison with the Mandinga, Malinké and Bambara languages. As to be expected most are found to be closest to the Mandinga version spoken in Guiné Bissau & Gambia.

However some words are more related to interior versions, Bambara spoken in Mali and Malinké mostly in Guiné Conakry. This incl. the very significant words of Kodé (meaning youngest child) and Bombu meaning the practice of carrying infants on their mother’s backs. Of course this doesn’t have to mean per se that Cape Verdean Crioulo got these words from interior Mande speakers. It could also be that these words are no longer used among coastal Mande speakers because they became “old fashioned” and got replaced by other words.

***

***

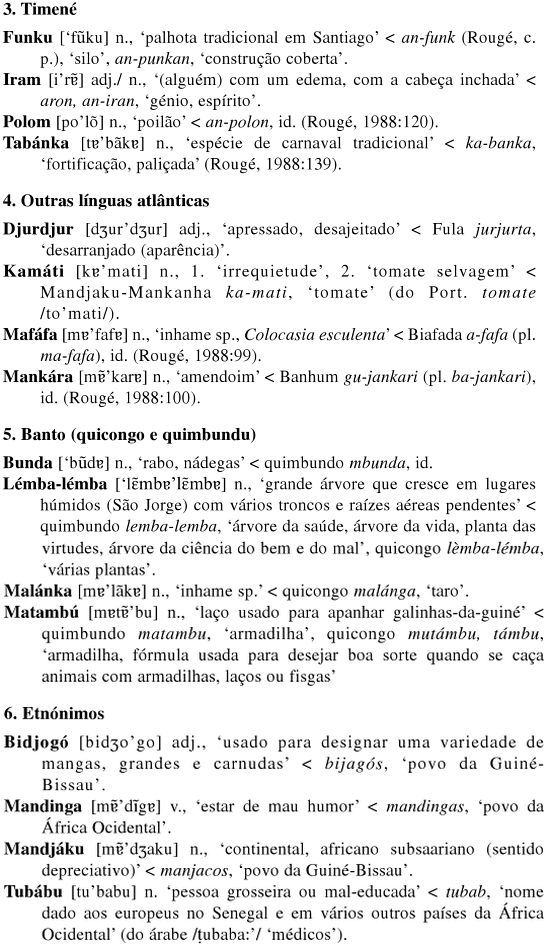

Also interesting the finding of some words with Temné (=Timiné) origins from Sierra Leone. The number in itself is quite small but the words are highly significant for Cape Verdean culture. Especially Tabanka (=musical style/festival but originally meaning fortified village) & Funco (=traditional type of house building). Quint assumes it’s because Temne was such an important trading language at the time and not per se because of ancestral connections (he makes the same assumption for Mandinga). However I think there’s plenty evidence that both ethnically Temne (Sape) and ethnic Mandinga speakers were present in Cape Verde to pass on this linguistical influence directly.

____________________

“Timene is the least known by those who have studied the Cape Verdean language. It’s a language that is now spoken in the north of Sierra Leone, in the extreme south of what was then the Captaincy of Cape Verde. Currently it is a language with a vehicular role that is much less important than in that time, in which it was the most commonly used language in the cola nut trade. Indeed, cola nuts are still the base product for the marriage dowry negotiation process in all of West Africa. Because of this important role in people’s social lives, a lot of people knew how to speak Timene.” ____________________The remaining list is made up of 1 word each for Fula, Banhun, Beafada, Manjak (Papel). As future research continues it might very well be that more contributions from these languages will be found. Intriguingly there are also 4 words with possibly Kikongo or Kimbundo origin. Still caution is in order because a word like Bunda seems to have entered Cape Verdean Crioulo due to modernday contacts with Brazilians. While Lema-Lemba seems to be a tree that’s not native to Cape Verde but rather from São Tomé! Unfortunately we can’t say for any of these words how or when approximately they might have entered Cape Verdean Crioulo. Languages being flexible and not static they incorporate new words all the time and through various ways.

***

***

Lang (2011)

He’s basically arguing for a linguistically founding effect of the early Wolof majority among Cape Verde’s population based on semantic and gramatical similarity.

____________________

Wolof speakers, as is suggested in the grammar of SC (Santiago Crioulo). This idea is also not refuted by the fact that the lexemes of Manding origin seem to be more numerous in SC than those of Wolof origin (see below): the Wolof slaves laid the structural foundations of SC [Santiago Crioulo] to which those who arrived later had to conform, but the merchants and the slaves who came from more southerly regions were able to continue to introduce African vocabulary following the end of the period of trade with the Wolofs.”

“A few cases of simple relexification of elements from Wolof in Santiago Creole suggest that the Wolofs were the dominant linguistic group amongst the “creolisers” in Santiago. Two arguments taken from the history of the slave trade will be proposed to confirm this hypothesis. In a final section, we present a case of the survival, in a simplified form, of a verbal category of Wolof in Santiago Creole: The imperfective variety of the Wolof ‘situative’ survives in a semantically simplified form in the progressive of Santiago Creole. Both categories are marked by a series of two verbal particles, the second of which is the marker of imperfectivity. However, the Santiago Creole progressive has retained only the progressive meaning of the imperfective variety of the Wolof ‘situative’, abandoning its ‘situative’ meaning. Such cases suggest that, in the creolisation process, the language structures of the group dominant amongst the creolisers more often survive in a modified form (generally, simplified) than as simple calques. Arguably, these modifications/simplifications are intended to ease the joining of other groups.”**

____________________

***

Jacobs (2010)

Arguing in favour for a Cape Verdean origin of the related Crioulo spoken in Guiné Bissau and Casamance. Basically due to the constant flow of Cape Verdean lançados/traders, priests, military, officials etc. to Guiné Bissau. He thinks the shared words of Wolof origins found in both creoles could only have been introduced by way of Cape Verdean Crioulo. Wolof not having any direct connections with Guiné Bissau historically speaking.

____________________

“Of course, three factors that might hamper a proper assessment of the Wolof

contribution should be acknowledged: firstly, Wolof is by far the best documented

language within the branch of Atlantic languages. This might color the results of

etymological research in favor of Wolof. Secondly, as noted by Kihm, ‘we only have

access to the present forms of the languages, and there is no guarantee that they

have not changed since the time they were substratally active’ (1989: 35). Thirdly,

through centuries of contact, Mandinka and the surrounding Atlantic languages

have borrowed lexically from one another. […]

On the other hand, Kihm also provided arguments that make it safe to assume

that the African languages ‘remained more or less the same’ (1989: 35) over the last

three to four centuries. And we may also recall that Rouge (1999a: 56) — an absolute

authority in etymological research on the Portuguese-based creoles (cf. Rouge

2004a) — believes that the etymology of the 11 Wolof items ‘nao deixa duvida

alguma’ [‘is beyond doubt’]. We therefore need not doubt that Wolof was indeed a

major contributor to UGPC’s African lexicon and it seems justified to take Rouge’s

etymological survey as representative.

____________________

***

Verdu et al. (2017)

This is a highly fascinating study which combines genetics with linguistics for a sample group from Santiago (n=44). I will therefore discuss its main genetic findings in the DNA Evidence section. The study doesn’t really do a proper deep-dive into the question of specific African origins of Crioulo (beyond Gambian Mandinka). But it does suggest that Crioulo as spoken by Cape Verdeans with a higher degree of African admixture will also feature more African linguistic influences. Intuitively this seems somewhat logical. Given that the more heavily Afro-descended segments of the population would have retained more of their African heritage. Also culturally speaking. While people with predominant European ancestry will often (but not always!) have been socialized to adapt more Portuguese influences. Ultimately leading to decreolization.

Furthermore especially for Santiago it is known that so-called Badiu communities in the remote interior have historically speaking been somewhat isolated from coastal communities and also other islands. The term Badiu originally referring to runaway slaves. However they also frequently intermarried with manumitted slaves. On the other hand it should be noted that this study only relies on the Crioulo variant as spoken on Santiago. On other islands there might be different or additional “Africanisms”. This is still a somewhat understudied field. Although most likely Santiago will indeed have the highest degree of African linguistic influence. But still for example on the Barlavento islands but also Fogo the correlation might not be that strong when using a locally adapted Crioulo dataset. Also to be taken into consideration is that nowadays so-called decreolization is probably increasing among all segments of the population and all islands. Regrettably so, due to the effect of massmedia.

____________________

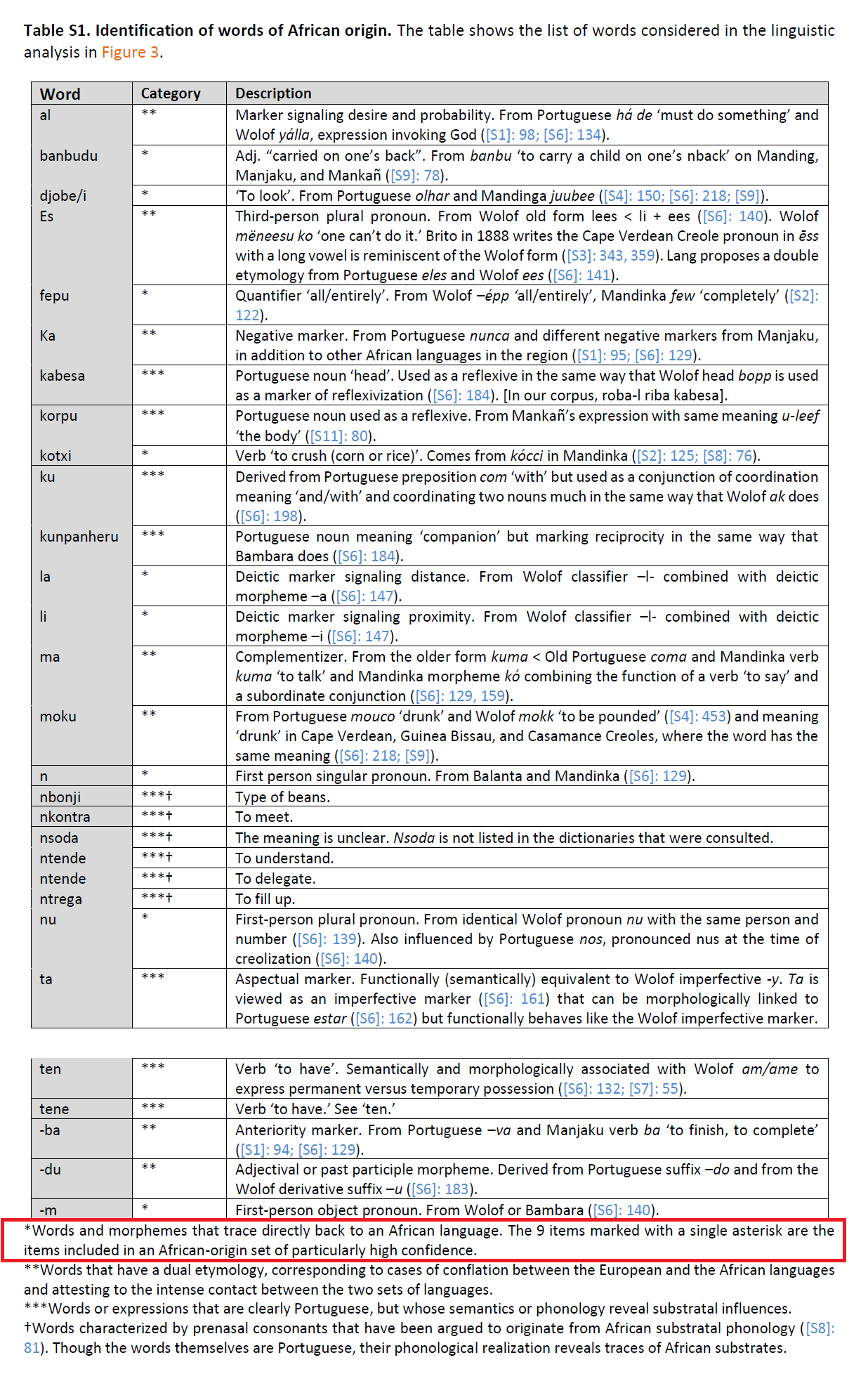

“we computed an African linguistic score that measures the degree to which each individual used a set of 212 lexical items (henceforth ‘‘words’’) that correspond to instances of 29 underlying high-confidence African-origin roots and morphemes“ (Verdu et al, 2017, p.2529)

“African genetic admixture proportions and African linguistic admixture scores for our 212-word set have a significant correlation among Kriolu speakers. Many of the individuals with the lowest African genetic ancestries have among the lowest African linguistic admixture scores, and African linguistic admixture scores are greatest for many individuals with high African genetic ancestries.” (Verdu et al, 2017, p.2531)

“That the genetic signal accords with the character of Cape Verdean Kriolu as a mixture of Portuguese and Senegambian languages supports the use of inferences of genetic ancestry in creole populations as a means of generating hypotheses about linguistic ancestry and provides evidence supporting Mandinka contributions to the Kriolu language.

The fact that Gambian Mandinka are genetically more similar to the Cape Verdean sample than are Senegalese Mandenka is of interest for the study of fine-scale origins of Cape Verdean Kriolu. Their languages are from the same language family, unlike more linguistically distant source languages such as Wolof; in assessments of Kriolu origins that take genetics into account, it will be of interest to also consider genetic data on Wolof-speaking populations.” (Verdu et al, 2017, p.2532)

____________________

See below for an overview of the African-origins words used in their research.

***

Undoubtedly with more research this intriguing topic will be further clarified. In fact there has already been one follow-up study in 2023 by the same researchteam (see this link). This time the Cape Verdean reference panel covers all islands (n=225). However they are still using the same Santiago-biased linguistic dataset. Hence the outcomes are quite similar as obtained in 2017 and do not reveal any major novelty. The correlation although positive actually appears to be rather weak (Spearman ρ=0.2070, p=0.0018, see this figure). However this researchfield of how linguistics may correlate with genetics remains very captivating! I am looking forward to more insights. One of the involved researchers, Marlyse Baptista, is currently working on a new publication together with Ousmane Cisse.